Small decisions that can lead to unexpected outcomes

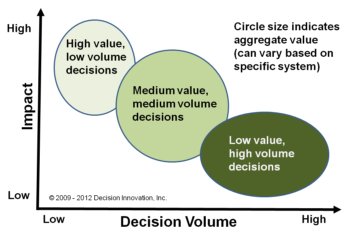

Large value decisions inherently suggest that the magnitude of the potential consequences will be high. However, as you move lower in a decision network, the number of small decisions being made increases in number, making it possible for the combined value of these small choices to exceed the value of the larger decisions. Is it possible that these smaller decisions can be made in a way that works against the benefits projected in a higher level decision?

Large value decisions inherently suggest that the magnitude of the potential consequences will be high. However, as you move lower in a decision network, the number of small decisions being made increases in number, making it possible for the combined value of these small choices to exceed the value of the larger decisions. Is it possible that these smaller decisions can be made in a way that works against the benefits projected in a higher level decision?

This idea has been explored at numerous times throughout history, with one early example being attributed to Aristotle (384-322 BC) in his thesis, "Politics." Related thinking is conveyed in many areas of research including economics, sociology, psychology, computer science, game theory, philosophy, and logic. More recent and popular references include:

- The "butterfly effect" from chaos theory (term coined by Edward Lenz)

- The "tyranny of small decisions" (from a 1966 essay by Alfred Kahn)

- The "tragedy of the commons" (from a 1968 article by Garret Hardin)

The problem with small decisions

Collectively, small decisions can add up to big results. This happens in all our decision types: business, consumer and personal. The recent economic crisis is often attributed to the unintended consequences of millions of smaller decisions that resulted from changes in government policy and regulation. The sum of all these small choices led to a housing and debt bubble that, when burst, had far reaching disastrous consequences across multiple regional economies.

Collectively, small decisions can add up to big results. This happens in all our decision types: business, consumer and personal. The recent economic crisis is often attributed to the unintended consequences of millions of smaller decisions that resulted from changes in government policy and regulation. The sum of all these small choices led to a housing and debt bubble that, when burst, had far reaching disastrous consequences across multiple regional economies.

Inattention to smaller decisions, particularly where there is a bias or preference for a decision to be made in the same way, can lead to a large unexpected outcome. A particularly alarming case is characterized as the dilemma of the "tragedy of the commons," where small independent decisions based on apparent rational self interest lead to the depletion of a common resource that opposes everyone's long term interest.

Some relevant examples

The potential impact of many small decisions is supported with examples throughout historical literature. Here are some examples for our various decision types.

For business:

- Approval decisions for purchases with credit and debit cards number in the tens of billions. The need to automate and manage this huge number of transaction decisions has been a key driver in the development of Enterprise Decision Management (EDM) applications.

- Many cases of environmental change and endangerment of species can be traced back to small decisions.

- People making calls at the same time at a football game or large concert due to a specific event can overload the phone system and cause a system outage or failure.

For consumer:

For consumer:

- Routine small credit card purchases can lead to an unmanageable debt load.

- An overabundance of choice has led to an increase in consumer anxiety.

- Routine choices of a specific brand can increase costs when new alternatives are not considered that may provide equal benefit. Generic drugs are an example.

For personal:

- Daily or weekly decisions to eat out can break budgets.

- Small decisions can lead to destructive habits and addictions such as alcoholism, or eating fast food.

- Dealing with emails at work. You start out focused on business related emails and end up consumed with personal emails that lead to your dismissal.

For community and government:

- Unplanned growth of a community has led to water shortages and increased water costs, particularly when many people decide to water their lawn during hot summers.

- Local decisions made to enable growth (without long-term planning) have led to areas of extreme traffic congestion.

Recognize that the unexpected outcome of a collection of decisions can lead to a beneficial outcome as well. Problems help to bring focus to the unintended or unexpected nature of the consequences. The goal is to identify improvements to the decision making process to consistently achieve more outcomes that are intended.

What causes the problem?

Taking a systems thinking perspective can help reveal some of the possible causes for dilemmas resulting from small decisions. These include:

- Discrepancy in timeframes - Larger decisions, such as strategic or policy decisions, are often made for longer timeframes. Small choices made in frequent short timeframes (such as small purchase decisions) might be made differently if awareness of longer term consequences (such as removal of a desired choice) is understood.

- Decisions not consciously made - Small decisions can become habit. Sometimes these decisions need to be raised to a conscious level.

- Amplifications that aren't considered or are ignored - Social networks have made this more apparent. Simple choices, such as poorly thought statements, can go viral and generate unintended consequences.

- Not considering or ignoring cumulative effects - This is equivalent to ignoring the "bigger picture", or failing to ask the question, "What would happen if the same choice is made every time?"

- Failure to consider external costs and benefits

- A bias toward reductionism - People want to break problems down and push smaller decisions down. The idiom "not see the forest for the trees" reflects this loss in seeing the greater whole or system view.

- Failure to see dependence - Small decisions are often viewed (or modeled) to be independent when they actually do have dependent relationships. (See our decision making model)

Preventing problems with small decisions

Estimates of daily decision making suggest that we make thousands of choices every day. Here are some ideas that can help prevent these small choices from creating unintended consequences and outcomes.

Create and protect appropriate layers of decision making. Don't lose site of the bigger picture decisions that should influence your choice.

Create and protect appropriate layers of decision making. Don't lose site of the bigger picture decisions that should influence your choice.- Apply systems thinking to common decisions that could be made in a similar way. If the effects of a choice are amplified, what would happen? Consider extreme cases.

- Create decision rules for choices that are made often.

- Automate decisions where appropriate.

- Consider different timeframes. What if I make this decision once, many times in a week, many times in a year, …?

- Consider the external benefits and costs of a decision, particularly with regard to shared resources.

- Remove shared resource limitations (this is often accomplished with new technology)

- Create habits for little choices that create positive results.

- Likewise, occasionally examine habits to determine that they are generating intended outcomes.

The cumulative impact of small decisions can create significant outcomes. A Connected Decisions™ framework can help manage these decisions to achieve desired results while preventing unintended consequences.

References:

Hardin, Garret. "The Tragedy of the Commons". Science 162 (3859): 1243-1248. 1968.

Kahn, Alfred E. "The Tyranny of Small Decisions: Market Failures, Imperfections, and the Limits of Economics". Kyklos, 19: 23-47. 1966