Decision timing - How to get it right and prevent major decision traps

Once a problem presents itself or the need for a decision is identified, one of the most important questions that needs to be answered is, "When is the decision or resolution needed?" Decision timing can vary widely; from mere seconds/minutes for first responder emergencies, to years for long range strategic initiatives or major life choices.

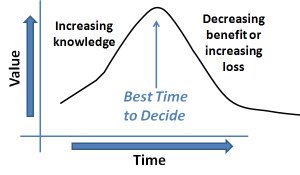

The image to the right helps visualize the competing forces at work when trying to find the best time to reach a decision. Too little time and the decision is made without knowledge that could have enabled a more informed choice, generally reducing risk. Too much time and the benefits from the alternative solutions are delayed, or in the case of a problem, losses or pain continue to increase.

The image to the right helps visualize the competing forces at work when trying to find the best time to reach a decision. Too little time and the decision is made without knowledge that could have enabled a more informed choice, generally reducing risk. Too much time and the benefits from the alternative solutions are delayed, or in the case of a problem, losses or pain continue to increase.

The lack of making a decision in a timely matter (being indecisive) often means that all or most of the best options have been eliminated, and you are only left with the least beneficial option(s). For example, if you delay your decision to apply to colleges, you are often left with the options that have late application dates, but none of these would have been your first choice.

Common decision traps and errors related to decision timing

The decision value graph helps provides a sense of detachment with regard to choosing when to decide, but in reality, there are significant emotions at play.

Here are some of the common decision errors, biases or characterizations associated with choosing too early:

- Shooting from the hip - being impulsive or plunging in (Russo, Schoemaker, 1990) without adequate information

- Planning fallacy - the bias toward underestimating how long actions will take

- Primacy effect - the tendency to weigh initial events more than latter events which would promote a quicker decision

- Immediate gratification - people tend to prefer immediate payoffs over later payoffs, and this increases as payoffs get closer

- Neglect of risk - the inclination to completely disregard probability or risk when making uncertain decisions

- Herd instinct - common bias to adopt the views and follow the behaviors of the majority

- Shortsighted shortcuts (Russo, Schoemaker, 1990) - relying too heavily on convenient facts or easily obtained information

Correspondingly, here are some of the common traps, biases or depictions associated with deciding too late:

- Analysis paralysis or information bias - the tendency to seek information that can not affect the outcome or being more focused on the process than the result

- Procrastination - waiting too long to gather information

- Maintaining the status quo or complacency

- Recency effect - the mistake of weighting recent events higher than earlier events which could encourage a delayed decision

- Normalcy bias - rejecting the need to react or plan for a failure or disaster that has never happened before

Internal and external knowledge

From the graph, we can see that the optimal point for making a decision occurs at the balance point between taking sufficient time to obtain the required knowledge to choose effectively and avoiding the loss in benefit (or increase in pain) due to delaying the choice. As you might suspect, finding this optimum is rarely achieved in practice.

Generally, gathering the information that would enable objective evaluation of the alternative solutions can be difficult and costly. However, acquiring the internal knowledge (individually or within an organization) that would characterize the success factors or goals for the decision is a minimum that must be achieved to have any hope for making an effective choice. Not obtaining this more easily gathered internal knowledge is like starting a search without determining what you are looking for.

A good decision making process will ensure the development of these criteria (success factors), and in the event that the desired objective data is not available for the alternative solutions, at least the subjective analysis will be evaluated against the factors or goals that would likely lead to a preferred outcome. Good decision making tools will also accelerate the information gathering effort by reusing knowledge gained from similar and related decision making efforts.

Finding out what we don't know we don't know

Difficult and highly complex decisions can often lead to information gathering efforts that can have serious negative impact on decision timing. Often times this is a result of exposing just how little is known about the possible consequences of the solution alternatives that are being analyzed. In this case, some effort is needed along a solution path to expose what "we don't know we don't know".

In these cases, it is important to consider approaches to mitigate the value loss that comes as a result of the delayed decision. A few strategies that can be used include:

- Initiate lower cost exploratory efforts along the paths of solution alternatives where high uncertainty exists due to lack of knowledge

- Make the decision and proceed along the preferred solution alternative with checkpoints in place that would force a new decision based on knowledge gained through decision execution

- Take actions to reduce the known negative consequences resulting from the decision timing delay

Some hints to improve decision timing

In Bill Jensen's book "Simplicity - The New Competitive Advantage", research is presented addressing the question "How do people really make decisions?" He extracts the following pattern from surveys of more than 2500 people:

"Everyone from the most junior to the most senior had just 5 questions that when answered led to action.

- How is this [decision] relevant to what I do?

- What, specifically should I do?

- How will I be measured, and what are the consequences?

- What tools and support are available?

- WIIFM - What's In It For Me? For us? "

Question #4 was identified as being the most important, suggesting the increasing need for decision making tools that can help deal with the cognitive overload that results from information that is doubling every three years.

Reference:

Russo, J., and Schoemaker, P. (1990, October). Decision Traps - The Ten Barriers to Brilliant Decision-Making and How to Overcome Them.